|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

02-10-06: Sean Williams' 'The Crooked Letter' & Williams-Dix 'Geodesica: Descent' |

||||||

Booking

the Cataclysm

What's quite interesting is what's on offer here, an unusual contemporary fantasy that to this reader is quite reminiscent of the work of Tim Powers. Since Powers occupies the top echelon of our auto-buy list, work that is even reminiscent of his gets real serious attention. Sean Williams is probably best known over here for a series of PBO space operas written with Shane Dix. There's the Orphans of Earth trilogy, the Evergence trilogy and the 'Geodesica' novels; 'Geodesica: Ascent' and now 'Geodesica: Descent' (Ace / Penguin Putnam ; January 31, 2006 ; $7.99). Williams and Dix are writing first-class MMPB space opera, chock full of what we've come to hope for; antagonists, allies and alien artifacts in perfectly balanced doses. This latest entry sports a blurb from Alastair Reynolds which is probably all many of us need to aid in parting us with our cash. But readers longing for something slightly more in the mainstream might find themselves quite intrigued by 'The Crooked Letter'. It begins with "mirror twins" Seth and Hadrian Castillo. When Seth is murdered, the slow countdown to the Apocalypse picks up speed, and the two of them find out what many believe to be true; that our reality is but one of many, and some folks can travel between them. All it takes is a little bit of death. What Williams has done is infuse our world with a synthesis of many mythologies. Readers will find all the familiar genre fiction tag words here, re-invented and re-invigorated by Williams' fusion. Expect to meet just about any entity you've met in speculative fiction, from the Elohim to vampires, from gods to "Ghul (aka Jinn) and the Feie (aka Charites, Gratiae, Kuretes)". There are more, lots more, many, one might hope, catalogued in the three appendices that follow the novel proper.

Williams slices and dices religious, ethnic and folk traditions with élan. You find everything from Albanian folklore to Cabbalistic notions to Tripolitanian riffs in 'The Crooked Letter' and more Biblical quotes than a politician's speech. Well, maybe not the latter. Still, Williams emphasizes that he has quoted liberally, with small liberties and often even literally from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible. Maybe he should run for office; but he'll have to limit his ambitions to governor, at least, as of this date. The real question here is the Series question, always a heady, difficult conundrum. Do you start the series before the second book is out? In this case, probably yes, in part, because, as the author tells us in his note at the end of the book, "the exact sequence of the novels depends on the way that you look at them." We're told that 'The Crooked Letter' is in fact a prequel, of sorts, to his series 'The Books of the Change' published in Australia back in 2001-2002. We're told that he's already started on the second book; well, in that he has a title, the evocative -of-monsters 'Chimaera'. That book, we're told is a sequel to both 'The Crooked Letter' and the entire series 'The Books of the Change'. By the way, it was only a couple of days ago that I suggested that artist Greg Bridges would be worth watching, in reference to his cover for Liz Williams' 'Darkland'. Well, here’s another Williams and another Bridges. While it may be a time sink, here’s the link to Bridges' website. If nothing else, I know my own tastes! So what to do, readers? My take is to get in line to buy up the hardcover edition of 'The Crooked Letter', read that, then head directly in the Australian series, 'the Books of the Change'. That should keep us going at least until 'Chimaera' shows up. And after that? Well, assuming the world has not ended, I'm guessing there will be a few more PBO space operas. And given that it is with this format and subject that the SF genre as we know it today was born, that's not a bad place to start anew, or even end up. And as well, we've learned a Valuable Lesson: keep your eyes on Australian fiction. I'm feeling edified already! |

|

02-09-06: Fallout Shelters |

||||||

Jay

McInerney's 'The Good Life' and Brian Shawver's 'Aftermath'

Who are we now? We are the consequences of our own actions. We are the result of the hard work we did, of the ill-advised choices we made. And as consequences, it's no surprise that we are interested in consequences, and given what we are, it's no surprise that we see ourselves in mirrors such as 'Aftermath' by Brian Shawver (Nan A. Talese / Doubleday ; January 31, 2006 ; $23.95) and 'The Good Life' by Jay McInerney (Alfred A. Knopf ; February 6, 2006 ; $25.00). We're looking backward and inward. Now that we've lived some kind of a life, now that we’ve drained ourselves of color, we can see things in black and white and gray. In books. Shawver and McInerney have both turned their vision inward. We've all blown up our lives, or had them blown up for us, and these writers have joined us in the back yard, looking down with fear, with longing at the fallout shelters that are now our lives, the protective coating we’ve given ourselves in order to deal with what we've become. In Shawver's novel the inciting incident is small-scale and personal, while in McInerney's novel it's nothing less than the events of September 11, 2001. No matter. Lives can be shattered at any magnification. The telescope and the microscope are equally merciless, equally intent on showing simply what is there. 'Aftermath' is where we all live. It's the town, the city, the street, the families that surround us. Set in a Pennsylvania suburb, Shawver's novel begins when Colin Chase, the popular kid we all hated in high school (unless we were that person), is injured in a fight outside a small diner on a Friday night. You know those nights. Kids hanging out, taunting one another. When the fight breaks out, Casey Fielder, the chump who owns the restaurant, he just tries to ignore it. Never calls the police. But Colin's not just been knocked down. He's brain damaged, and Fielder is going to be punished to the full extent of the law. Every decision, no matter how small it seems at the time, how innocuous, has consequences. Casey's about to find that out.

I find it fascinating that both of these novels take their main characters into the darkness via not simply their action, but the effects of their actions and their inactions. This is not an uncommon theme in literature. It's been around since the Greeks first put on masks. But in today's world, our fiction seems so concerned with action. I'm not talking simply about kick-down-the-doors action, but to me, so much of what we read involves getting out and doing something, like finding the criminal, killing the monster, or seeking the truth. And the upshot of these actions is not often examined, it's left to the imagination, or a sequel that simply restarts the action. 'Aftermath' has a particularly poignant premise, in that it is based not on what the characters do, but what they don't do. Casey does not report a fight; Colin's mother never really gets to know her son. Inaction begets the characters' journeys across a landscape divided by economic disparity. Shawver's novel will require the reader to buck up before and after. This is not a story of happiness. There are consequences to reading the novel as well. McInerney is a bit more willing to allow the reader some leeway, some buoyancy, but it's not an easy journey. His characters, returning from the presciently titled 'Brightness Falls' are not the smart alecks that peopled his earlier novels. They’ve been through the wringer at this point in their lives. Happiness is visible, but it too will have consequences and alas, unhappiness may be one of them. Though it's probably just coincidence, there's another similarity between the novels. Both covers show us a landscape covered in fallout. There's no shelter, not beneath the backyard, and not in the mineshafts that Doctor Strangelove fled to so long ago. Those bright and shiny atom bombs were pretty great. They were decisive. There were no worries about surviving. No matter what you did you ended up as a shadow on the sidewalk. So, should you read these books? I can't decide for you, but it's worth considering a break in the cavalcade of genre fiction I generally find myself talking about and reading. I heard McInerney interviewed by Terry Gross, and immediately went home to pick up this book. To be perfectly honest, I'd not been all that interested in reading it or writing about it, but the interview changed my mind, and it pointed out the value of interviews to me. It may seem odd, but when I interview authors, I'm already plunged so deeply into the writer and their work that it never occurs to me the effect an interview might have on one not so deeply immersed. Hearing Gross talk to McInerney once again reminded me that those conversations can really help draw readers towards writers they might enjoy, but would otherwise miss. So here's my suggestion. If you can, listen to the interview here. Or if not, pop on down to your own version of the Capitola Book Café, or Logos, or Bookshop Santa Cruz, or The Literary Guillotine. Pick up the book, read the words. Yes, I'm well aware. There will be consequences. |

|

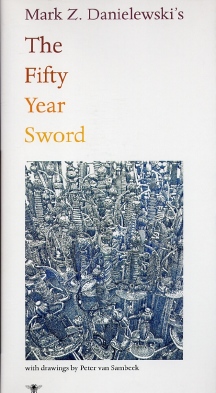

02-08-06: Mark Z. Danielewski's 'The Fifty Year Sword' |

||||||

The

Thing Itself

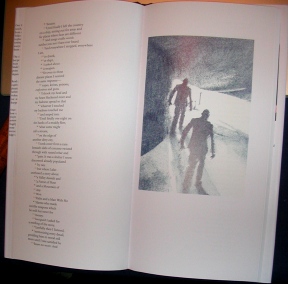

So, I promised a follow up about Mark Z. Danielewski's 'The Fifty Year Sword', and here it is, or rather there it has been, sitting on the Rolling Shelves while readers awaited word. Here is the word. Weird. Mark Z. Danielewski is a writer of Weird Fiction. Now, this is not a Review of this book, but rather a Preview, so that the prospective buyer can more accurately determine whether or not they should spend the $55 for this slim volume. First off, I'll talk about the buying process. I generally don’t link to buying sites. In this case, however, buying is pertinent to this article. This is not a book that your local independent bookseller will stock, or even, given my recent search, your typical online bookseller. You're best off buying it via the instructions given here. The copies easily available online start at $224.95 for precisely the same book you can get for $55, and go up to $1,000.00 for a copy of the same book that is, "One of only 51 signed and numbered copies. This copy signed with 3 large "Z" in different color ink." Should those Z's make a $945 difference worthwhile to you, have at it. You know where and how to look. Otherwise, follow the instructions given at the link, which is a discussion forum about Danielewksi's work. I'm here to attest that it's not easy to buy this book, even if you follow those instructions. I'm also here to suggest that should you attempt to buy this book, you should probably buy two copies at the outset, and save yourself the trouble of going back a second time. When I first bought the damn thing, as soon as I completed the process, I realized that I wanted a second copy. I then, immediately, while still "logged in" the *.*-like server tried to do so, but was stymied at every pass. I even killed the session, restarted the browser, but, no, no, it wasn't going to let me order. I got into some loop wherein it seemed I had ordered it, or was on the verge of being able to order it, and tried to but nothing happened. In a sense this was good, because for a while I was afraid I'd accidentally ordered like, six copies. That proved not to be the case. After a few iterations of the buy loop, I gave up, decided to wait until the book arrived. Only when I received the first copy did I go back and buy two more. Then it all seemed to work very well. I suppose the fact that I ordered two additional copies should tell you something beyond your first conjectures that I'm independently wealthy (utterly wrong) and/or somewhat loony and compulsive when it comes to book buying (probably a fair cop).

First and foremost, this is a book by the man who wrote 'House of Leaves'. If that book simply annoyed you, then you'll find this book, though much smaller, probably equally annoying. But if that book enthralled you, if that book set your mind afire and heavily engaged your book-buying sensibility, then what are you waiting for? Oh, right, me. Well, from the get-go, it's officially titled "Mark Z. Danielewski's The Fifty Year Sword." Kind of like Mark Z. Danielewski thinks of himself as a movie director, and while there's a good deal of hubris in that thought it's not beyond the pale, considering what's on offer here. It's an odd-sized book, so you won’t be getting a clean scan. At 6 7/16" by 12 7/8" (6.5 x 13, sort of), it's too big to fit into the flat-bed scanner. Now, with many books I entirely avoid reading the dust jacket verbiage. Here, I think it’s a good idea. I'm going to reproduce it word-for-word.

OKEY DOKEY! Trust

me on this, I haven’t given

away the game at all. This is Mark Z. Danielewski, and that means any

clue to some real-world

chain of events is only obliquely of help in deciphering the narrative.

In fact, there is a sort of introduction, wherein someone describes

five

characters and explains one aspect of the text; that is that there

are five colors of quotation marks, which roughly correspond to five

speakers.

Sort of. That aspect I'll allow to remain mysterious. The title page

actually says "Mark Z. Danielewski's The Fifty Year Sword by" and

then displays five different-colored quotation marks. At the bottom

of what

I'm calling the introduction, the speaker thereof claims, "to

here present a pretty peculiar and perhaps altogether alternate history

of

one October evening in East Texas." |

|

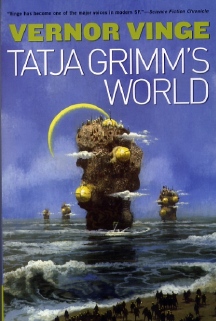

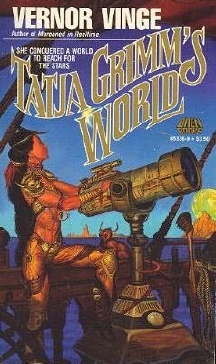

02-07-06: Vernor Vinge Re-Visits 'Tatja Grimm's World' |

|||||||||

Berkley

to Baen To Tor

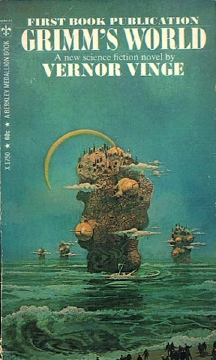

I'm not saying the art is not well done. Perhaps it is too well done. It's like someone beamed it straight out of the 1970's. And what's weird is, the book itself is beamed, well not straight out of the 1970's, but circuitously out of the late 1960's. So, what is this 'Tatja Grimm's World', beyond the traditional re-issue of a now well-known author's early work? It's a story with layers, a story in which the story in the book and the story of the book have a few parallels. So, the story in the book. On a world that is not the world we know -- but is enough like it to have science fiction magazines, Rey Guile edits Fantasie, an SF magazine with an albatross around its neck. That would be the adventures of Hrala, the Barbarian Queen, the kind of second-rate stuff that sells a lot of copies but irritates Guile's finer literary instincts. In order to promote the albatross, he hires one Tatja Grimm. At least that's what he thinks her name is; he can barely pronounce what she says, and what she says doesn't matter a lot. It's what she does that makes the difference, and how she looks in the wigs, because Tatja is going to play Hrala. But though she comes from a background that's comparatively primitive to those who are printing Fantasie, Tatja is not without intelligence or ambition. She might sign up, but it won’t be where she ends up. I mean, life as a science fiction story heroine -- who ever heard of such a thing!

Instead, expect what we in the science fiction reviewing business call a "fix-up" novel, or in this case, a fix-up of a fix-up. Let's rewind. In 1966, John W. Campbell prints "The Barbarian Princess" in Analog. It had to help that the story has as a main character a man who edits a science fiction magazine. It’s certainly a clever way to open the door, and something that readers of SF magazines had to find interesting -- and still would. Then, in 1968, Damon Knight (who wrote a wonderful biography of Charles Fort) published "Grimm's Story" in 'Orbit 4'. And finally, 'Grimm's Story' appeared with what became Part III of this novel in 'Grimm's World', a 1969 Berkley Books PBO. The colophon page of the current novel shows the last copyright ("first published") by Baen Books in 1987.

The cover art for this version of 'Tatja Grimm's World' is a very nicely restored version of the art for the Berkley PBO version from 1969. Heck, if that cover art wanted to, it could have a pretty decent little family by now, a house, mortgage, a couple of kids. And here is where all the layers come together. The story of Tatja Grimm, from a hardscrabble girl-on-the-ground to 'The Feral Child', (part III of this version of the novel) is stitched together, inextricably linked with the artwork that has accompanied it since it was first published. Tor has rescued not just the novel itself, but the cover art and given it a new life. No, 'Tatja Grimm's World' may not be the Vinge you know in any sense. But for Tor to bring a first novel by the now-famous Vinge to life with the 1970's-style cover art intact? That's outstanding! It's as if a story from Fantasie has come to pass. One hopes that Rey Guile would at least give this budding author, this Vinge guy a chance. One day, he may invent the world. |

|

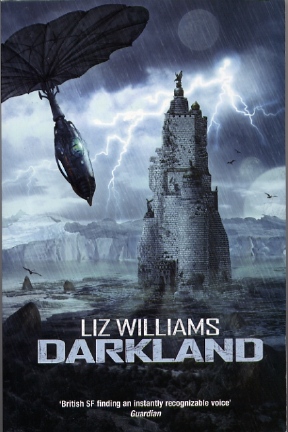

02-06-06: Liz Williams Visits 'Darkland'; The Chemistry of Fear |

|||

SF Gothic

Williams has been forging a career in the difficult standalone science fiction novel market. It can't be easy. Unlike so many of her contemporaries, her novels are all pretty much insular one-offs, requiring that she re-build the entire universe in each book. You won’t find subtitles on her novels that tell you, "The new mumble-mumble Universe book!" or "The new Sci-Fi-name-here novel!" No, Liz Williams works from scratch every time, ensuring that readers are not ready for the surprises she has in store for them. This is not to say that her novels seem scattered or disparate. Williams has a very unique and identifiable sensibility, and your best clue to that sensibility comes from the bit about her parents. Her work is distinctly theatrical and certifiably gothic. But it's also set in carefully imagined distant futures, and consistently character-centric. This last trait is why she's so special. Williams writes about the basics, about people we care about and can understand, even when they live in a future where technology and space exploration have utterly transformed humans into something that seems almost alien. Williams does other really, really well. In this case, other is the world of Nhem. Vali Hallsdottir is an assassin sent on a mission to bring down an unpleasant regime. Of course, this being the far future, nought is what it seems to be, especially her partner and one-time lover, Frey. The genetic transformations he's undergone for this assignment seems to have changed him more than intended, and Valli finds herself pursuing him into Darkland, where something very other awaits them both. Here's what's great about 'Darkland'. No fuss, no muss, murky science fiction mysteries spin out in Williams' unique and distinctly feminine voice. You get the ground-level perspective, the wonderful science-fictional immersion in another world that reads like a gothic-horror novel written by someone who lives in another world, another time. Williams isn’t writing about the future so much as she seems to be sending back tales from the futures in which she lives. It's a subtle distinction that makes an unsubtle difference. These are not stories about the future and the people who live in strange times. These are strange stories about people who happen to live in Williams' detailed, weirdly imagined futures. It helps that Williams does not go on forever; at 308 pages, 'Darkland' is nothing if not concise. And Tor UK has helped as well, offering readers a beautiful, readable package with a great cover by Greg Bridges. This is the way science fiction should be published. 'Darkland' is a prose stage, and Williams is a gothic actress. You'll get the whole message in one act. Sit down, put the spotlight on the words. The show is about to begin. UPDATE: Here's a link sent in by a reader explaining that this novel is the first in a series. In the August 2005 interview with Sioned Wynn of The Druid Network, Williams states: "My novel DARKLAND will be out with Tor Macmillan in February in this country, and I'm working on the sequel, which involves a female serial killer (in space), Icelandic and Norse mythology, and questions of consciousness and gender." |

|||

A Conversation With Leslie Ellen Jones

Fortunately for me, I just have to show up. Jones does all the heavy lifting, and we talk about the origins of Wicca, which are not at all what you might think them to be. Jones, who often contributes to the Fortean list, will turn your head with regards to what you might have thought about witches and their place in society. Jones and I also talked about the origins of storytelling, folklore, the Greek myths and even the brain chemistry of fear. There's a reason why your parents are always trying to scare you -- it works. Jones explained why, and she uttered the great phrase: "warning fictions". What more could you ask than to find the origins of the modern horror story in "warning fictions"? I've uploaded the usual MP3 and RealAudio files. If you're subscribed to the podcast, you've already downloaded this. If not, Jones is a great reason to start listening and the perfect example of how our experience of fiction is informed by the world of non-fiction. That is, if you want some fodder for your Next Great American Horror Novel, you’d do well to pick up 'From Witch to Wicca'. Or if you want to get an angle on the underpinnings of the last Great American Horror Novel you read, here is the place to do so. Doctor Jones has arrived in mind surgery. Don’t mind the scalpel. It's shiny and bright. This won’t hurt a bit. |