|

|

|

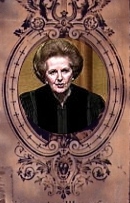

| M.

Thatcher |

Tastes of Blackness

Since the start of the world there have been three main types of

darkness: (1) Cimmerian Darkness, from between the years when the

ocean drank Atlantis and the years of the rise of the sons of Aryas

, which can only be cut by barbarian swords and barbarian mirth,

(2) the Heart of Darkness, invented in Belgium for export and still

used to flavour pralines and other expensive chocolates, (3) the

Hair of Darkness, glimpsed in a vision by the blasphemous prophet

Hakim Mokanna and described as belonging to a terrible demoness

or usurped goddess seated on an uncomfortable throne in a roofless

house at the centre of a distant island who visibly sagged under

the weight of her impossible organic crown, a cone of grotesque

flaxen locks that towered into the sky and actually touched a point

of the firmament directly opposite the position of the sun on the

far side of the world. Hakim gasped and the image vanished and

not even his most devout followers, those who accepted that revulsion

was a cardinal virtue, attributed any importance to such a ridiculously

vile apparition. Whatever the intensity, whether thick glooms or

thin twilights or moderate dusks, whether they occasion blinking

or groping, like certain ladies, chiefly of the night, sometimes

of the morning, all other kinds of darkness are merely variations

on this Trinity of Murks.

Gross Conception

At the precise instant that the Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva

was conducting the maiden flight of his first autogyro, a child

was conceived in the drab industrial town of Grantham, England.

The gestation and delivery were hard and unnaturally long for the

mother. The father was a grocer notorious for selling the oldest

vegetables in the region and a rumour soon began to be circulated

that even the fruit of his loins was outdated and rotten. The parents

chose to name the baby Margaret and could not explain why. On the

night of the autumn equinox 1926, a gigantic explosion shook the

chimneypots of Grantham’s houses, for a chemical plant had

caught fire on the outskirts, sending a vast cloud of sulphur dioxide

drifting over the town. In order to alleviate the stink of his

putrefying stock, the grocer had already thrown wide every door

and window in his shop and remained unaware that his sleeping daughter

upstairs was gulping in enormous quantities of the sulphurous gas.

In the morning he found her half dead in her cot, the whites of

her eyes permanently stained a rancid yellow, her tongue bloated

and horrible, her hands twisted into claws. But sulphur is good

for the skin and after she recovered, her scalp never itched, no

matter how inhuman her subsequent hairstyles. Also she developed

an early interest in chemistry.

The Oxford Test-Tube

The altered child had no wish to remain in her home town and work

behind the counter in her father’s miserable shop taking

money from senile customers and giving the withered produce of

poisoned allotments in exchange. In her opinion, the only counters

worth her time were counter-revolutions, though her political ideas

were far from being formed at this early stage. In class she was

a mediocre pupil, but in her spare time, while other children played

with balls and dolls, she experimented in the privacy of her bedroom

with chemicals stolen from school. The ceilings of Number 2, North

Parade, Grantham, still bear the blotches of her enigmatic research,

although the building itself has now been converted into a restaurant

and guest house. What she was trying to achieve by mixing sulphuric

and nitric acids with glycerine in flasks immersed in bowls of

ice is still uncertain. Her later claim that she was attempting

to synthesise and stockpile vast quantities of hair dye is dubious

but cannot be entirely discounted. She eventually passed enough

exams with high enough grades to win a place at Oxford University.

At Oxford she was an unremarkable student, but in her spare time, while other

undergraduates played with punting, cocaine and fornication, she remained alone

behind a locked door reading the political philosophy of such thinkers as Edmund

Burke, Count Gobineau and Houston Stewart Chamberlain. She cultivated no friends

and attended no parties but one of her lecturers claimed she once confided in

him an interest in applying the rules of chemistry to society, a notion at which

he sneered, causing her to withdraw even more deeply into her own world. It was

the beginning of the Cold War, tensions between the liberal democracies of the

West and the New Empire of Russia were constantly increasing, helicopters and

other rotating-wing aircraft filled a sky already sleepily pricked by a thousand

dreaming towers. At night, after the blood of sunset had dripped all away over

the table-edge of the horizon, she stalked the corridors of her college, her

shadow on the far wall magnified by the thin rays of light coming from the keyholes

of occupied rooms, her silhouette crouched and leering with outstretched talons,

but half its height taken up by the penumbra of her hairdo. Frustrated, she was

trying to menace the laughter, tinkle of glasses and bed squeakings of her normal

neighbours.

Research, Revulsion and Taxes

|

|

M.

Hatcher.

|

In 1947, having received her degree, the future Prime Minister of Great Britain

embarked on a course of postgraduate work and study, specialising in stabilising

volatile compounds to enable them to be transported more effectively. She applied

herself with relish to this task for almost four years until an overheard conversation

between the directors of the laboratory revealed to her the nature of what she

had never thought to ask, namely the ultimate purpose of her research. The volatile

compounds in question were medicines, not toxins or explosives, and the aim of

stabilising them was to ensure they might be carried long distances by motorbikes

or helicopters without damage. A mere prototype herself, Thatcher promptly resigned

and looked for an alternative career. She found one as a tax lawyer.

She became an expert at exploiting loopholes in the existing legislation, helping

certain firms and individuals avoid paying tax at the expense of other firms

and individuals. She particularly favoured the manufacturers of weapons and pesticides,

tobacco companies and the largest supermarket chains, and enjoyed penalising

anything ethical or aesthetic. Her blood still contained particles of sulphur.

A mysterious group of anonymous economists granted her an unknown prize in a

secret ceremony at an undisclosed location but she was never made aware of it.

Somehow she succeeded in encouraging a rewrite of the law so that helicopters

used for humanitarian purposes had to pay extra tax while those used by the military

became exempt from paying anything at all. One unexpected consequence of this

action was an interest among engineers in developing variations on single sets

of rotors to create machines that might not be defined as helicopters. The manufacturers

of humanitarian helicopters were forced to pursue these projects through penury,

the manufacturers of military helicopters did so because they could now afford

to innovate. A second unknown prize was granted in circumstances possibly similar

to the first.

Successful but curiously dissatisfied, the still fledgling Thatcher determined

to enjoy a more active social life. She wandered the streets of London, the ‘Big

Smoke’ in contemporary parlance, through the thick fogs, but looked in

vain for nightlife, chancing only on strange establishments where people convulsed

their bodies to sounds and ingested fermented sugars in liquid form with formulae

she knew. She passed on. Eventually she discovered a nightclub and entered the

open door, feeling at home immediately and realising that not only was a social

life possible even for her but easy. She entered a chamber where people were

sitting facing a stage on which stood a very old man. He was mumbling something

about free trade, selective franchise, minority rule and the perennial justice

of the status quo. How she enjoyed herself among these ravers! That night she

became an official member of the Conservative Party and a year later the wife

of another regular attendee at every meeting of the party, a rich drunkard and

gambler named after a common model of fire engine. Dennis provided the wealth

for her eternally grasping hands and she numbed his hangovers by shouting, a

mutually beneficial, if totally horrific, symbiosis. The marriage ceremony may

also have been secret and unknown. Nobody can say for sure.

House of Abnormal Commons

|

|

|

| M.

Hatchet |

Helicopters come and go but Thatcher remained in one place, at the heart of conservatism,

a Member of Parliament and a shrieking crone on the backbenches at Westminster,

her hair piled higher than ever, her jowls juddering incessantly, the wrinkles

on her neck multiplying daily. Her yellow eyes sickly flickered like living kidney

stones. The first satellites were being launched into orbit by Russia and her

agitation at not being able to simply reach up and pluck these instruments of

deceit from the very heavens was palpable. Thoughts of outer space chilled the

vacuum in her soul.

Despite her ambition and her husband’s wealth, her rise through the ranks

was slow, slower than the decay of a preserved cadaver, at least as slow as the

healing of a trade unionist mangled by faulty machinery, but perhaps not quite

as slow as the evolution of the pig. The benches of Parliament creaked timidly

under her greasy buttocks. Ten years as a minor figure in politics enraged her

senses, invoked her ire and gave her an abiding hatred for the word ‘minor’ however

it was spelled. Much later she would come to hate the word ‘major’ also,

but by that time it was too late. As she grew ineffectually older, her hair continued

to mount higher on her head until the weight began to deform her skull, the pressure

forcing her bulging eyes to point in different directions, giving the illusion

they could watch everything at once.

Finally in 1970, after waiting more than a decade, she was promoted to the rank

of Minister of Education and Science. That year there was no summer.

Udder Considerations

It must not be supposed that Margaret Thatcher possessed no sense of fun. She

laughed for a week when England launched its own first satellite and commissioned

a group of early electronic musicians to compose a piece as a tribute to this

achievement. Named after the satellite itself, ‘Telestar’ became

a moderate hit for sonic experimentalist Joe Meek. Had it only been a minor hit

she would have arranged his assassination. As it was, Meek committed suicide

in despair at what he had done, inheriting neither the earth nor the royalties

from his tune. Another escapade was the rustling of a herd of cows with a handful

of loyal followers during the darkness of a powercut, an adventure which earned

her the nickname ‘Thatcher the Milk Snatcher’. She also enjoyed squatting

on rotting vegetables.

The Blasted Heath

The defeat of the Conservative Party in the general elections of 1974 sent shockwaves

through the secret clubs of economists and manipulators who pulled, or imagined

they pulled, the hidden strings of government. With the disgrace of Prime Minister

Edward Heath and his expulsion from the walnut and teak corridors of power, they

needed a substitute champion, or replacement puppet. Thatcher, so to speak, was

their man. They encouraged her to announce her intention to apply for leadership

of the party and following a phoney secret ballot she won the post in 1975. At

this time, with the aid of her mysterious friends, she embarked on a program

of image management, learning how to lower her voice an octave, improving her

posture by reducing the weight on her skeleton by secreting miniature helium

balloons in her hairdo and adopting a handbag as a mascot, the contents of which

have still never been authenticated .

Across a landscape decimated by civil unrest, strikes, energy deficits, congealed

rubbish, crumbling housing estates, rusty factories, hideous pop groups, ships

stranded on hillocks, huge rats, radioactive rivers, cardboard boxes, rancid

butter mountains, colleges without doors or windows, queues of starving immigrants,

congested hospitals, empty libraries, deformed policemen, bruised wives, shallow

graves, chopper bicycles and allotments littered with the limbs of plastic dolls

and half burned pages of laminated pornographic magazines, Thatcher trundled

in her private train, the roof bristling with anti-aircraft guns and sentries

with binoculars watching out for helicopters. It was inevitable the Conservatives

would win the next election. Her dominance was assured. Her megaphoned cries

of evil joy burst the eardrums of rabbits and yokels in the passing fields and

villages.

Ships That Pass in the Night…

Having secured the support of the middle classes by various crude or subtle measures,

Thatcher won a landslide victory in the general elections of 1979 and celebrated

in style by arranging a real landslide in a Welsh valley with a form of dynamite

she invented herself, burying an entire school full of children under a million

metric tonnes of rubble. Certain regions of her new kingdom proved to be more

troublesome than others. These regions all had one thing in common: they were

areas where miners lived and worked. She already loathed this word but who were

miners and what did they do? Thatcher decided to investigate and came away horrified.

These miners were people who dug up inflammable black stones from the bowels

of the earth, drilling down ever deeper in their quest for the magic lumps, approaching

dangerously close to the infernal regions, which she regarded as her personal

territory. “Not over my backyard!” she roared as she vowed to destroy

the mining industry. One morning without realising it, she met the King of the

Miners in the street, both blown along by their personal ill-winds, filling the

open coats of the other as they passed like the frightful sails of plague ships.

… and get Blown to Bits

Before war could be declared on the miners, Thatcher found it necessary to practise

on a distant country. The foolish Argentinian dictator, General Galtieri, assuming

that because the British leader was a woman she would fight guns with flowers,

sent an army of boys in watertight boots to occupy the Sebald Islands, a Dutch

possession in the South Atlantic claimed under different names by both Britain

and Argentina. For Thatcher the invasion was a superb opportunity to increase

her prestige and make money. Factories churned out bombs and shells containing

propellants and charges on which she held the patents. The British fleet steamed

south, each ship packed to the brim with sailors, soldiers, missiles, hunting

dogs and jet aircraft. Only helicopters were not permitted to enter the conflict.

After a British submarine sank the largest Argentinian ship, the Yerba Mate,

General Galtieri surrendered and committed himself to a lunatic asylum. The great

writer Jorge Luis Borges compared the war to “two bald men arguing over

a comb.” The massive hairstyle of Thatcher cast an oily shadow over this

comment as she ordered the burning of his books in revenge. On the Sebald Islands

charred sheep cooled slowly.

Feverish with bloodlust, Thatcher turned her attention to the miners and within

a year had annihilated them. Arthur, King of the Miners, also known as the ‘Once

and Future Striker’, offered to switch sides just before the end. Thatcher

welcomed him with open arms and invited him to her private residence, a mansion

with gardens in which all the plants were only black or white, like moral questions.

When Arthur arrived at ‘Checkers’ he was met by Thatcher herself

who led him up flights of steps to the flat roof of the building. There was a

magnificent view of boring England. Arthur bowed down before her and Thatcher

drew a sword from a scabbard which hung at her waist. The King of the Miners

was knighted with a single stroke, his unbelieving head rolling to the edge of

the roof and falling onto the patio far below, shattering like the eggs which

formed the major part of the diet of his betrayed followers. Thatcher sheathed

the sword without wiping it. She had commissioned the weapon from a master swordsmith

in Sheffield, a town not far behind Damascus and Toledo in its reputation for

the excellence and durability of its sharpened steel. In a moment of pomposity

, she had named this weapon the ‘Sword of Truth’. Once drawn it could

only be sheathed after an outrageous lie had been told.

It was with this sword that Thatcher encouraged her husband Dennis to dance frantically

about a hotel room in Brighton during the Conservative Party conference of 1984,

using it to beat time on the furniture, poking his shadow on the walls, conducting

a wild but silent melody which deafened the drunken man and sent him reeling

in circles while they both laughed hysterically in the mirror above the bed.

This performance was interrupted by an enormous explosion. The Irish Republican

Army, known in their own language as the Feigned Shin, had planted a bomb in

the hotel, hoping to wipe out the entire government. The plot was a failure.

In the steaming rubble Thatcher sneered defiance at her enemies, a single tiny

bruise above her left eye scintillating in the flashing lights of the ambulances,

police vehicles and fire engines. Janitors came to mop the blood of insignificant

conservatives. Then Thatcher sheathed the ‘Sword of Truth’. Everyone

blinked. It seemed that the explosion had never happened, that it had been nothing

but an outrageous lie.

Sayings of Thatcher: a Selection

(1) “There is no such thing as a molecule: there are only individual atoms.”

(2) “Homeless people are those you step over on the way to the opera.”

(3) “Nobody would remember the Good Samaritan if he had only had good intentions.

He also owned a large business and traded weapons across the border.”

(4) “In politics, if you want anything said, ask a man. If you want anything

done, ask a woman. If you want anything illegal, ask Jeffery Archer.”

(5) “The Pole Tax will be a vote winner.”

(6) “This lady is not for turning or any other form of rotational manipulation.”

(7) “Read my lips: new taxes for deaf people!”

(8) “I am a very friendly person. I know dictators all over the world.”

The Pole Tax Riots

|

|

N.

Ratchet.

|

In her final years of power, Thatcher devoted her time to inventing cruel new

taxes to harass and depress the people. She began charging homeless citizens

rent for using the sky as a roof to sleep under. But her grandest scheme was

the cutting down of the famous Sherwood Forest in Hampshire to make a sharpened

pole for every inhabitant of her country. The Pole Tax was an amazingly simple

concept. All men, women and children, regardless of age, financial circumstances

or mental capacity, were required to pay a monthly sum of Fifty Guineas or else

be decapitated and have their heads impaled on the pole that bore their name.

Riots erupted in the streets, students and office workers and shopkeepers running

up and down the twisting alleyways of London, over the monumental bridges, banging

drums and firing rocket propelled grenades at policemen and judges. Thatcher

watched impassively from a window. Dennis remained loyal but the other members

of the Conservative Party turned against her one at a time. Finally a leadership

challenge was launched. The secret group of economists who pulled the strings

had decided to abandon her. Tears in her eyes, she resigned rather than lose

face. Her real face had already lost all resemblance to a human visage and that

was enough.

The man who replaced her, John Major, led the Conservative Party to another victory

in the following General Elections, but the party was never as strong as it had

been under Thatcher. Despite his iron grey hair and cold square spectacles, Major

was ultimately a feeble autocrat. He had little interest in poison gas. His brother

was a leading authority on the subject of garden gnomes. Coincidentally, it was

rumoured that the Lord of Gnomes had a brother who collected models of British

Prime Ministers. Major occasionally went to ‘Checkers’ to visit Thatcher

but these trips became more and more infrequent. She had slumped into a deep

armchair and deeper depression, her hairstyle now so tall and heavy it had to

be supported from the ceiling by chains. The ceiling already sagged under the

strain, plaster flaking down on the carpet like the dandruff of a senile mammoth.

Her Final Winter

Thatcher lingered in this world for another decade, spending her last year in

bed, propped up on pillows. The ceiling had completely collapsed around her and

as she rolled her eyes up to the open sky she dimly wondered if this exposure

to nature defined her as homeless. From outside, a passing walker might squint

at what seemed to be an enormous bush sprouting from the centre of a ruined house.

Dennis had long since vanished into one of the numerous taverns which lurk in

every corner of rural England. She never saw him again. When she died, something

extraordinary happened, something almost predicted by the prophet Hakim Mokanna

all those centuries before. Her hairstyle detached itself from her scalp and

floated up into the sky, blocking the sun like a monstrously diabolical cloud.

A chilly darkness spread across the land. Crops failed and people starved. Finally

an enterprising pilot flew a helicopter with contra-rotating blades into the

middle of the aerial hairstyle, cutting it away like a barber of justice. Sunlight

was restored but the millions of tiny hairs which fell to earth were blown around

the world and stuck in the eyes and hearts of innocent people, causing them to

see and feel everything in free market terms.

|

|