|

|

A nice blurry picture of my shelf of Abyss books. |

|

|

|

The Agony Column for May 15, 209903

Commentary and Interviews by Rick Kleffel

A long while back, I set out on a quest inspired by a conversation with my wife while driving the car about to pick up the kids. I was trying to explain to her my enchantment with the old Dell Abyss books. Were these books based on the movie she asked? Yikes, I said. No! It was famous horror imprint in the 1980's - they're those paperbacks taking up an entire shelf in the living room. An entire shelf?! What's an imprint? she asked.

|

|

A nice blurry picture of my shelf of Abyss books. |

And thus are born writing projects. Well, with a lot of help from some of the top pros in the business. I managed to contact Jeanne Cavelos, the curator and creator of Abyss. When I first started really, really getting into horror, Abyss defined the scope of much of what I read. From the long view, Abyss brought us a number of authors who are still highly regarded, and brought them to the paperback rack of your grocery store. That's where I found Kathe Koja, Brian Hodge and even, eventually, Michael McDowell's 'Toplin', with the illustrations by J. K. Potter intact. It was unprecedented, and few have followed so strongly since those halcyon days. Abyss books bring back a lot of memories of intense and pleasurable reading. More recently, Jeanne is the author of six well-regarded novels and runs the Odyssey Writing Workshop.

But my history with imprints goes back a lot farther than that. Like most of us, I've been reading Ace SF forever. So I was honored when Ginjer Buchanan, now the top editor over at Ace, also agreed to answer my questions. Ace - what can I say? It's like a monument and still is - Ace just brought us the latest Alastair Reynolds novel, 'Redemption Ark', the latest Simon R. Green novel, the first a six-volume version of Chaz Brenchley's horror-fantasy epic and the latest Patricia McKillip book - and that was just this week!

Pull up a chair and enjoy the history of great publishing with two of the best.

First, Jeanne Cavelos:

|

|

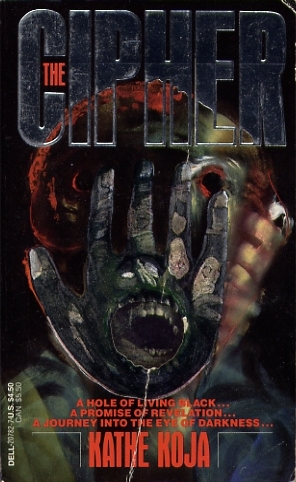

The first novel released by Jeanne Cavelos under the Abyss imprint broke a lot of preconceived notions about horror. |

TAC: What is an imprint?

JC: "Imprint" used to mean the name of the publisher. But as publishers have grown, merging with other publishers and releasing more and more books each month, "imprint" has come to mean the name of a line of books released by the publisher. For example, Random House publishes many imprints, including Random House, Doubleday, Delacorte, Dial, Bantam, Dell, Ballantine, Crown, and Fodor's. In many cases, these imprints have become so large that "sub-imprints" have been created. For example, Ballantine's books are divided into imprints such as Ballantine, Del Rey, Fawcett, Ivy, and One World.

An imprint helps bookstores--and sometimes readers--get a general idea of what kind of book they are looking at. If it's a Delacorte book, then it's a hardcover, and it's commercial fiction or nonfiction. If it's Fodor's, then it's probably a trade paperback travel book. As we talk about smaller imprints or "sub-imprints," the focus gets even more specific. Del Rey publishes only science fiction/fantasy.

Bookstores and book distributors can use imprints to help them figure out how many copies of a book to order. If an author is a known quantity, then bookstores will decide on the quantity to order based on the author's track record. But in the case of a new author, bookstores often look at the typical sales level of the imprint to decide how many copies of a book to order. Most readers don't pay much attention to imprints. The ones they do notice tend to be the smaller, more focused ones, which gain a sort of brand identity. Many science-fiction readers can tell you that DAW science fiction is much different than Tor science fiction, which is different than Del Rey science fiction. Each program has a somewhat different focus, in part because the editors have different tastes, and in part because each has found success with slightly different books, and so they focus on the type of books that have worked for them in the past.

|

|

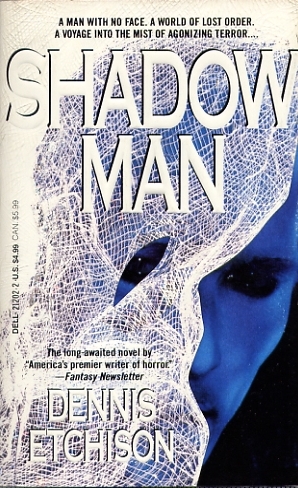

Dennis Etchison was one of the already-established authors published by Abyss; his work was a natural fit for the dark, urban visions that typified the imprint. |

TAC: Could you give me your pocket history of imprints in the publishing world at large and in genre fiction in specific?

JC: I started out working in the religious department at Doubleday, which was then an imprint of Bantam Doubleday Dell. Hardcover religious books were published under the Doubleday imprint, while paperback religious books were published under the Image imprint. Then I moved to Dell, another imprint of the company. I acquired books that were published under a number of Dell's imprints, including Delacorte, DTP, Delta, and Laurel.

I founded two new imprints while I was at Dell: Abyss, a line of sophisticated, psychological horror novels, and Cutting Edge, a line of literary, noir thrillers.

Creating these imprints, rather than just publishing the books under the existing imprints, brought them additional attention, both within the publishing company and without. The imprints also served as a signal to bookstores and the public that we were doing something new and different. With so many books being published each month, it's very hard to get attention for any one, and usually the publisher doesn't have the budget to heavily market or publicize a single title. By creating an imprint, the publishing house focuses attention on a group of books, and so can devote more money to the group than it would be able to spend on any one book. In the case of Abyss, we also needed to divorce ourselves from our own sales history. Dell had been publishing poor quality horror novels for some years--because no editor had a real interest in horror--and their sales were very low. If we were to continue publishing horror, then we had to improve the quality of our books. But even if we did, how would bookstores and readers get the message? How could we get bookstores to order more copies than our previous horror novels had sold, and how could we get readers to buy them? We needed to make a complete break with the past, and the way to do that was create a new imprint that would have a different identity--a new name, new authors, new cover treatments, new marketing plans, and a consistently high quality that would allow us to regain the faith and loyalty of readers.

|

|

Brian Hodge has more recently written some well-received novels of suspense, and has a collection of stories out from Night Shade books. |

TAC: Could you talk about the difference between a small-press publisher and an imprint of a larger publisher?

JC: Both may reflect the specific taste of the editor or editors, and may have an identifiable focus. The main difference is really in resources. A small-press publisher will be limited in what projects it can acquire. It won't be publishing the next Danielle Steele novel or John Grisham thriller (unless it's a special collector's edition). It can't afford to pay those authors, and even if it could, it doesn't have the ability to get books out in the quantities necessary--it doesn't have sufficient printing capacity, warehousing, the necessary sales force, or distribution network. So the small presses tend to focus on market niches that are smaller and more consistent, rather than taking the big gambles or pushing out the huge numbers that the major publishers do. Small presses tend to focus on nonfiction. When they go into fiction, they tend to stick with proven authors. The small publishers will also be more limited in their marketing and publicity. But then, many of the books published by large houses get virtually no marketing or publicity these days.

|

|

Note the ever-present Stephen King cover blurb. |

TAC: How is the fiction for an imprint selected?

JC: A small imprint needs to create a strong, consistent identity. The focus of the imprint needs to remain one of the primary considerations when an editor is reading submissions. High quality is also very important. You don't want to create brand name recognition only to have the reader decide he hates your brand and will avoid it like the plague. It's also very important--and I suppose obvious--to select books that you think will sell well. Authors with good sales histories are always a help. If two or three books of a new imprint don't sell well, the imprint can quickly fail.

TAC: How is the marketing for an imprint created?

JC: A budget needs to be established, which would be done over the course of numerous meetings between the editor, editor-in-chief, publisher, and heads of sales, marketing, and publicity. The budget, of course, depends on how well the books in the imprint are selling. For a new imprint, this is basically a guess. Based on the enthusiasm of those involved, a budget would be set to promote the launch, and then the marketing and publicity money would decline somewhat after that. These days, publishers don't spend a lot on marketing and publicity, except for their very top titles. So the editor needs to be creative and work with the other departments to stretch each dollar as far as possible.

|

|

Lisa Tuttle has a collaboration with George R. R. Martin that's been recently reprinted. |

TAC: What imprints are you watching and why?

JC: Dial publishes some absolutely wonderful fiction--fresh and thought provoking. I also like to take a look at whatever Nan A. Talese* puts out, which is generally of a very high quality. A couple new imprints I'm curious about are Atria and TalkMiramax. And a new small publisher whose been putting out some interesting books is Rugged Land.

Thanks, Jeanne. This is fascinating stuff.

[*And you should too - Nan A. Talese just brought you James Frey's 'A Million Little Pieces', which as of last week, was the number one non-fiction bestseller in the Bay Area, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.]

|

|

Ginjer can be happy that Alastair Reynolds latest novel is worthy of the great reviews and awards that it is sure to win. |

And now Ginjer Buchanan brings us her perspective.....

TAC: What is an imprint?

GB: It's always a designation on a spine. It can represent either the name of the paperback line (here, that would be Berkley, Jove and Ace, which is not a subset of Berkley, but its own line of books.) Or it can indicate a particular kind of book within a line. Our mystery imprint is (Berkley) Prime Crime, there is a new romance imprint called (Berkley) Sensation, the Berkley YA books are done as Berkley Jam, and media tie-ins are Berkley Boulevard. Sometimes in hardcover, a specific editor will be given a "boutique" imprint, a list of books that are all his or hers, and that have a specific name. That's rare in mass market, however.

TAC: Could you give me your pocket history of imprints in the publishing world at large and in genre fiction in specific?

GB: I suppose when it all started, there were just the names of the companies/lines, like Pocket Books and Bantam. (Ace in fact did things other than sf when it was first founded.) Anyway, as mass market publishing grew, companies decided to create specific genre imprints within their lines. It's a form of shorthand, really. And punchier than just using the word "mystery" or "fantasy" Actually, if anyone is interested, the PenguinPutnam website (www.penguinputnam.com) has a section with histories of all of the components of the company.

|

|

It's direct to mass market paperback for Simon R. Green's latest novel of supernatural comedy. |

TAC: Could you talk about the difference between a small-press publisher and an imprint of a larger publisher?

GB: There really is no difference between a small-press and a large publisher except for size, and all that entails. (Ability to buy, sell, print, warehouse and distribute more books.) So an imprint of that larger publisher has all of those advantages

TAC: How is the fiction for an imprint selected?

GB: By the editors. How else? (There are non-fiction imprints too, by the by. Mostly in hardcover and Trade.)

|

|

Here's 1/6 of Chaz Brenchley's fantasy trilogy. Horror writers are making a comeback -- but not too big. |

TAC: How is the marketing for an imprint created?

GB: There's a meeting which here is called the strategy meeting (it has other names in other places but it's the same meeting) where a whole bunch of people, including editorial, advertising promotion, publicity and sales go over a list of the upcoming books, a month at a time (we just had the October 2003 Strategy) and decide what to do for what books. So the marketing isn't attached to the imprint so much as to the book.

TAC: What imprints are you watching and why?

|

|

Patricia A. McKillip is a highly regarded fantasy writer published by Ginjer's Penguin/Putnam parent. |

GB: The as-yet-unnamed Harlequin romantic fantasy imprint, to see who they are publishing and how well they penetrate both the markets they are aiming at. If it works for them, as I believe it will, it will create marketing opportunities for us.

Thanks, Ginjer.

Now readers you too are ready to go forth and explain unto your spouses what precisely an imprint is - and why you have to buy every title in the line! Once you hook on to a good editor with superb taste - such as Ginjer, or Jeanne, or Simon Spanton at Victor Gollancz, Peter Lavery at Tor UK, or Darren Nash at Earthlight, you have yet another excellent tool for choosing the books that you read.

Thanks,

Rick Kleffel