|

|

Get past the racks of pretty paperbacks to the real meat of speculative fiction -- the non-fiction shelves. |

|

|

|

Forget the Fiction.

The Agony Column for November 23, 2002

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

|

|

Get past the racks of pretty paperbacks to the real meat of speculative fiction -- the non-fiction shelves. |

That's my advice. If you at least try to forget it, then you might be able to wrench your attention away from it long enough to see something else. The field of speculative fiction seems so crowded these days, so popular, that you'll find this harder than you think. Pass up the science fiction racks in your bookstore, and you'll end up in front of a bunch of thrillers or mysteries bulked up on technology that would make a 1950's sci-fi guy drool with envy. From its very birth, science fiction practically plateaued, the imaginations of its creators roped in by what science knew enough to ask questions about, even if it couldn't provide any reasonable answers. These days, the cyberpunks have become net.farts, looking to hook their boxcar up to the bio-train. Beyond that, quantum physics winks at writers on the horizon, alluring sexy, not virgin, but close enough for sci-fi. When you turn the volume up to eleven, who can tell the difference?

In such a saturated landscape, it's harder than you might think to clear your mind of preconceptions. If you read speculative fiction to experience that rush of newness and insight that you get from any great fiction, flavored with a dollop of strange, the first step to take is the one away from the SF shelves at your bookstore. That's pretty obvious. But when any fiction can be contaminated, what are your choices? That's pretty clear as well. To get a really fresh spin on the reading rush that good speculative fiction provides, you need to look for some speculative non-fiction.

|

|

Orson Welles paved the path for makers of the faux documentary with his historic broadcast of 'The War of the Worlds'. |

It's not the contradiction in terms it sounds to be. In fact, it's pretty damn prevalent in the field of speculative fiction and even in the cultural landscape. The most important piece of speculative non-fiction is Orson Welles Mercury Radio Broadcast of H. G. Wells' 'The War of the Worlds'. It stands as a brilliant conceptual art piece, and has inspired imitators still completing their works as I write this. Welles played on the very human suspicion that reality can alter in a single instant, that what we don't know -- do Martians (aliens) exist? -- can suddenly be known, and in that instant, reality can be transformed. He played with the remote broadcast capabilities of radio in a way that can never be duplicated. He set the standard for speculative non-fiction. Simply by using the broadcast medium, he made a science fiction writer's speculation come to life in the minds of his listeners. It changed the cultural landscape forever.

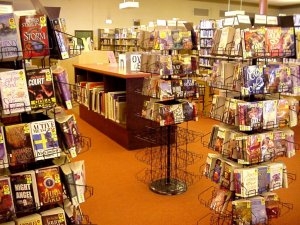

But speculative non-fiction isn't just for the brilliant innovators who break boundaries that can only be shattered once. It's also a big part of the ugly-dray workhorse that speculative fiction's fans don't want to admit keeps their favorite authors in enough money to produce a few good works. Those racks and racks of Science Fiction Paperbacks are made up of more than a little speculative non-fiction. In fact, I'd bet that speculative non-fiction makes up a pretty hefty bit of the business that keeps our favorite publishers afloat. After all, who can resist the allure of a 'Star *' Tech manual? If it's there in front of you, the browser in the bookstore or the guest in front of a coffee table, who can ignore the book and not open the covers?

|

|

These expensive and beautifully produced non-fiction works explain the workings of imaginary technology. No matter how cheesy the source, the concept is incredibly cool. |

Huge, glossy, immaculately produced, these staples of the SF shelves are getting more and more space. And say what you will about the value of the mega-creations upon which these manuals, visual dictionaries and whatnot are based, the books themselves are often rather lovely. Coffee table fodder need not be Art for the Ages. In fact, it's better if it's not. If you're going to buy something to glance at, sometimes you don't want heavyweight, hard-hitting imagery. Not only have I seen the burning monk, I've been the burning monk. It's not a place I care to return to.

|

|

|

|

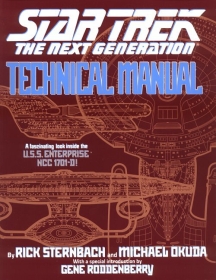

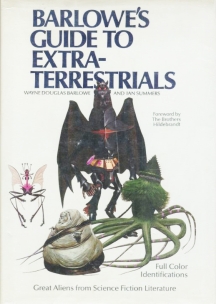

I went through two trade paperback versions of this book before I finally found a used hardcover in my favorite local used bookstore. |

This books promises and delivers a huge number of excellent paintings of alien life on a carefully conceived but really weird world. I love monsters, and I've spent a lot of time on Darwin IV. |

Like most folks, I'm not enamored of hell, but if I have to see it in a coffee table book, I'd prefer the artist to be Barlowe. |

On the other hand, there are more than a few coffee table books worth writing home about. Wayne Barlowe is the primary exponent of some of the best coffee-table speculative non-fiction you might hope to find. I can hardly imagine any speculative fiction reader who hasn't at least thumbed through 'Barlowe's Guide to Extraterrestrials' or 'Barlowe's Guide to Fantasy' while slumming in the Sci-Fi! Section of your local bookstore. But you might have missed 'Expedition: Being an Account in Words and Artwork of the 2358 A.D. Voyage to Darwin IV', an excellent example of speculative non-fiction in a large and wondrous format. Now, I can't claim to have actually read every word in this book, but I've spent enough time there to more than justify its cost. 'Expedition' is an illustrated notebook from a visit to an alien planet teeming with weird life. In case you think there's no analogue for the horror/fantasy end of the spectrum, think again; Barlowe also has 'Barlowe's Inferno' and 'Brushfire: Illuminations from the Inferno'. These are books that we might want to take for granted; they've been around for ages. But when you start to ponder what exactly they are, and where they fit in the speculative fiction/non-fiction world, they begin to seem quite a bit more interesting than they did when you thumbed through them at your local independent bookstore.

However wide the gap might be between Orson Welles and 'Star*' sharecropper art books, it's only a small part of the spectrum of speculative non-fiction. Recent releases on both sides of the spectrum amply demonstrate the full potential of this tiny niche to present the ready reader with a blast of new untainted by old. For this reader, speculative non-fiction starts out firmly in the non-fiction aisles of the bookstore, with works like Mike Davis' brilliant 'Dead Cities', Richard Preston's 'The Hot Zone' and George Dyson's 'Project Orion: The True Story of the Atomic Spaceship'. After a pleasurably mind-boggling flight through realms first charted by Borges, Calvino, and Lem, you're going to end up with the typical small-press production that breaks and builds boundaries with its excellence and invention, in this case, the Prime Books edition of Jeff Vandermeer's 'Cities of Saints and Madmen'. As a reader, you can stay in a small genre niche that somehow stretches from bright white non-fiction seen in a speculative light, to the impermeable darkness of fantastic speculation rendered as if it were unshakeable truth.

|

|

Mark Bowden's gripping and hilarious novel of a man who finds a million bucks should be on all your Christmas lists, whether as a gift to be received or given, it does not matter. |

Sometimes non-fiction is forced to speculate in the absence of verifiable facts or conflicting stories. The results can be as gripping, as entertaining as page-turningly compulsive as Mark Bowden's 'Finders Keepers'. Here's a two-hundred-something page book that reads like a novel and dances around the obfuscations of those who purport to be telling the truth. Bowden is a sharp, alluring prose writer. His story of an unemployed dock worker and methadrine addict who finds one million dollars in unmarked hundred dollar bills that falls off the back of an armored truck is nothing short of amazing. Nobody seems to be telling the whole truth, but Bowden gets there anyway, at least emotionally. This book is often hilarious and ultimately very sad. It's a one-sitting read. You might not even make it out of the bookstore, so be careful. Prepare to loan it to your friends.

|

|

|

Mike Davis can boggle your mind with non-fiction about the science-fictional aspects of our world. |

'The Dead Zone' -- Evocative photographs highlight Davis' no-hold-barred prose assault on nothing less than reality as we know, or rather accept it. |

"Sci fi happens," Mike Davis informs us in the opening essay for 'Dead Cities'. For those of us who came of age when the movie '2001' came out, then lived to see the year show few of the advances the movie made us care about so much, that's an understatement. I have a distinct memory of thinking that the 1970's would be for me "the future". Now they're the objects of puerile nostalgia. Davis grapples with this disconnect in essays that convey the science-fictional, surreal feel of the present. Published by the "not for profit" New Press, this collection is the perfect antidote for the mindless rush towards a capitalistic singularity that characterizes what that preservers of the status quo the misnamed "Reader's Digest" once called 'Life in These United States'. In his preface, 'The Flames of New York', Davis dredges up visions of skyscraper-shattering apocalypse from H. G. Wells 'The War in the Air' to the surrealist painting 'Los Muertos' by Jose Clemente Orozco. Davis' essay style is dense, but compulsively readable because they're partitioned off into small comprehensible chunks of concept and connection. They read almost like the info-dump from a great, undiscovered 1950's science fiction novel. He's an ardent advocate with a socialist's sense of justice.

The book itself is a pretty sweet production for a so-called "non-profit" press. It seems heftier than it ought to, as if the weight of the words within somehow increases the density of the pages themselves. My copy had some pages where a gray fog seems to permeate the paper, as if one of the many black and white photographs within had rubbed off from an opposing page; but these fogs occur on pages with no opposing picture. The illustrations are a wonderful bonus, evocative black and white photos that swing up out of the small-format like stones to smack the reader in the face with their images.

|

|

Davis made enemies in SoCal with the publication of his horror-movie landscape. |

This isn't Davis' only entry into speculative non-fiction. In his 1998 work 'The Ecology of Fear', he offers up the horror movie version of Los Angeles and its place in the Southern California landscape. This book attracted a notorious amount of attention when it was first released, rabidly attacked by "arts and letters" weeklies eager to protect their home turf and keep the tourists coming. Like "Dead Cities', it's an illustrated, thoughtful, and above all speculative look at how man is affecting a landscape and how the landscape is affecting man. Frank Herbert built a career in speculative fiction around these concepts. Mike Davis is even more fiercely intellectual, more of a rabble-rouser in a time when the rabble is feeling pretty crushed. Forget the not only the fiction, but the facts as well. It's the ideas that Mike Davis deals in. They're dangerous. They threaten life as we know it. What more can we ask from our reading?

|

|

|

This is probably the most familiar bit of speculative non-fiction. "Terrrifying" doesn't cover the half of it. |

In case we weren't scared enough by the bombardment of government warnings, Richard Preston tells us about the horrors of smallpox in his most recent book. |

Taking a step away from the intense intellectualism of Davis' non-fiction, one can easily, breezily enjoy the speculative non-fiction stylings of Richard Preston's 'The Hot Zone'. In fact, a quick comparison between that book and it's ridiculous follow-up, 'The Cobra Event' provides a day-and-night comparison of why speculative non-fiction is such a powerhouse. 'The Hot Zone' was the mega-bestselling story of an outbreak of the Ebola virus in an imported monkey-house in suburban Washington, DC. The potential for a nation-killing epidemic disease is painted in swift, sure strokes by Preston. It's everything a page-turning thriller should be, and everything a page-turning thriller cannot be -- true. It's a killer bit of research and a fantastic piece of speculative non-fiction that has the reader thinking "What if....?" long after they're finished reading what my brain wants to call "the novel". It's that tight and that good.

Of course, the effort to capitalize on all that fame was a novel, drearily bad and stilted, titled 'The Cobra Event'. It's surely nothing to write home about. One can hear the vast sucking sound as it absorbs all the ideas of Preston's non-fiction and leaves nothing but a chalky, bad film-treatment behind. Yes, it's a shame that the Ridley Scott production of 'The Hot Zone' was derailed by the as-bad-as-'The Cobra Event' movie 'Outbreak'. Still, no reason to dwell on Preston's single failure especially when he's working hard to compensate with the release of 'The Demon in the Freezer', his instant book to play on the government-induced hysteria about smallpox. It's certainly worth worrying about, and back in his safe ground of humanizing science, Preston turns in another bit of non-fiction where the reader-induced speculation is firmly on the terrorizing side.

|

|

|

John Keel is the acknowledged master of speculative non-fiction. This work is his masterpiece. |

How can you resist the title 'Disneyland of the Gods'? |

Not surprising, in this little sub genre there's a middle ground between the obvious non-fiction of Mike Davis and Richard Preston and wildly imaginative fiction of Jeff Vandermeer. Who better to occupy that middle ground than John Keel? Yes, he's only the latest to follow in the footsteps of Charles Fort, and yes, the work was adapted into a decent fictional concoction for the big screen, but in any evaluation, 'The Mothman Prophecies' has to stand tall. The writing style itself is mutant, but not half-moth, half-man. It's fact told as fiction, actual experience rendered with a larger-than-life pen and a feeling for the surreal that matches the best that any horror writer before or since has come up with. Most importantly, he approaches all this with a sense of humor that few before or after have matched. Look, I know it's hard to take any of this stuff seriously, he seems to say. It helps drive home his message that we live in a reality more malleable than we would like to admit.

|

|

Remember back when everyone was being abducted by aliens? The Sci-Fi channel wants you to, so their upcoming series gets the big ratings. This books looks at the human side of those times &endash; and humans are always the most fascinating monsters. |

Of course, you can go down the UFO/ghost/monster rathole and never escape. Pretty soon you'll find yourself in Urania. This is not a place I want to be as either a reader or a person. On the other hand, those who inhabit these ratholes either for a living or as an avocation can make a very fascinating subject. C. D. B. Bryan's 'Close Encounters of the Fourth Kind' is pretty entertaining series of portraits of these people and their claims. In 1995, just about everyone was being abducted by aliens. It was bigger than Disco. Bryan's portrait of some prime suspects in the abduction game is the perfect antidote the annoyingly gullible 'Abduction' by John Mack, which is the speculative non-fiction equivalent of an earnest but foolish hard SF tome.

Of course, some will want to present hard SF in the guise of speculative non-fiction, but I'm not having any of it. Hard SF has something that is anathema to speculative non-fiction: characters and plot. But don't leave hard SF authors out of the loop. Poland's own Stanislaw Lem is probably the singularly most prolific author of speculative non-fiction ever. He's also without doubt written much of the best speculative non-fiction, the stuff that points the way for all writers.

|

|

|

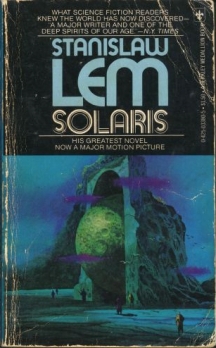

My original 'Solaris' movie tie-in paperback from 1971. That cover art isn't just typical 70's SF schlock, but an illustration of events from the novel. |

Well, as long as the author's name is on the front, and there's no abridged or adapted on there, they can't change the novel. Compare the covers -- you do the math. |

Lem is certainly best known for his novel 'Solaris', currently being hyped in movie form. But as I've said -- forget the fiction. To my mind, 'Solaris' is not his best novel (I'd vote for 'His Master's Voice'), and his novels certainly aren't his best writing. It's in his meta-fiction that Lem really shines. There are three essential collections that will give readers years of pleasure. These are some of the best-written, most complex, most re-readable books that you can invest in. They push the reader and the genre over an edge from which there is no return.

|

|

|

The recent paperback version of Lem's REAL masterpiece. |

My original hardcover, bought way back when from 'A Change of Hobbit' on Santa Monica Blvd. |

The most pertinent to our discussion is 'Imaginary Magnitude', published in Polish in 1981, and in English in 1984. Beautifully translated from the Polish by Marc E. Heine, this is a collection of introductions to textbooks of the future -- including itself. Lem's introduction is an elegant and thoughtful literary lampoon that laments "All the arts today are struggling to perform a rescue operation, for the universal expansion of creativity has become its curse, a race and an escape..." Lem makes the point that in writing only the introduction to a book, he leaves the reader's imagination free to create the actual work itself in any form the reader sees fit. This is a theme he'll return to again. But appropriately, it's only a tiny teaser for the wonders he's about to lay at the reader's feet in 'Imaginary Magnitude'.

In the Introduction to Reginald Gulliver's 'Eruntics', Lem amazingly, while writing speculative non-fiction, directly addresses the concept of speculative non-fiction and its relation to literature as a whole and science fiction in particular. "The book which I am introducing lies precisely in no man's land. It may be the result of lunacy, but in that case we are talking about a madness with precise methods; it may be the result pseudological perfidy, but then it would not be perfidious enough, for it would be unsalable. ....Bibliographies have listed this title under science fiction, but this area by now has become a dumping ground for all sorts of half-baked oddities...Were Plato to publish The Republic today, or Darwin The Origin of the Species, both books might bear the label "fantasy" whereupon they would be read by everybody but appreciated by nobody; sinking into sensational verbiage, they would play no part in the development of ideas...." Eruntics, as it happens, is the process of predicting the future by teaching bacteria the English language. This is done by using lasers to force bacteria to grow only in the form of Morse code dots and dashes. Lem's brilliant concept seizes upon language, science, literature, and publishing and throws them together in a final product that is hilarious and truly mind-boggling.

He doesn't stop there, and it keeps getting better. There's an Introduction, and an Introduction to the Second Edition of A History of Bitic Literature, that is, literature written by computers. Lem's explanation of how this comes about is quite fascinating. His prognostic abilities are amply displayed in the 'Proffertinc' for the 44 Volume Extelopedia, a self-changing encyclopedia that anticipated the web before it came to pass. The final and longest piece offers not only an introduction, but a forward, an afterword and an actual lecture by a Pentagon computer that becomes self-aware. Don't expect anything like Harlan Ellison's AM. Instead, look for a dense ontology of intelligence itself.

|

|

This collection of perfect reviews of non-existant books is another that is arguably Lem's best. Remember -- forget the fiction! |

Lem's first metafictional work had actually appeared earlier. 'A Perfect Vacuum', in which he offers 15 book reviews of non-existent books (and one of 'A Perfect Vacuum' itself) was published in Poland in 1971, and in the US in 1978. When it reviews itself, 'A Perfect Vacuum' is both rather harsh and fairly accurate; for each of the pieces "there was an idea that burst upon the author--and from which he shrank." No, Lem is doing nothing new here. Borges has reviewed books that don't exist, and much of his best fiction -- in particular the seminal 'Tlon Uqbar, Orbis Tertius' -- can be used to define speculative non-fiction. But 'A Perfect Vacuum' has so many fantastically funny and inventive reviews, and is so consistent in terms of quality --everything is spectacular -- that it clearly stands on its own. It covers more territory that most novels and includes some rather compelling characters -- both the authors of the books reviewed and the reviewers themselves are revealed in the text.

|

|

By the time this weird artifact was released, HBJ had a new cover stylist for Lem's stuff. But the speculative non-fiction inside is first rate and unchanged. |

Lem synthesizes these two books in 'One Human Minute', which features three reviews of books from the future. The title review allows Lem to revel in his statistical playground, pondering a version of the 'Guinness Book of World Records' that tells not the most or the best, but give statistics for how many humans are engaged in an activity in any given minute of the day. It's funny and interesting, but nowhere in the league of 'The Upside-Down Evolution', wherein Lem admits that he's come into possession of tome titled 'Weapons Systems of the 21st Century'. This is one frightening bit of speculation, much of which has already been set into motion. Lem addresses the problems with redundant systems ("..if a system has a million elements and each element will malfunction only one time in a million, a breakdown is certain.") and the problems with the current search for artificial intelligence ("Not artificial intelligence but artificial instinct should have been simulated for programming at the outset. Instinct appeared almost a billion years earlier than intelligence -- clear proof that it is easier to produce.") Few writers have Lem's ability to toss off pithy statements. Fewer still have the ability to do so and make the reader laugh. Lem's bleak sense of humor shines through all his writing.

|

|

What sort of man reads 'Playboy'? What sort of man reads 'Bikini Planet'? I'll never tell -- but if you bought this issue for the articles, you got a wonderful short-short by Thomas M. Disch. |

Stepping past Stanislaw Lem's synthetic non-fiction, we come to just about the end of the rope. First a quick shot back in time to one of the first bits of speculative non-fiction I ever encountered. It's December 1966. Playboy is a swingin' magazine with some great, and very weird fiction, including one little short, short story -- not a story really, a fake advertisement -- titled 'Cephalotron'. I'm too young to see it then, but I'm sure it was imprinted on my tiny brain somehow. So, when it gets published as the titular story in the Doubleday paperback by Thomas M. Disch, 'Fun With Your New Head', I'm right there picking it up. I'd be surprised, in fact, if the paperback isn't sitting out in the garage even now. (I looked but could not find it on first search.) It certainly made an impression on me. Disch returned to speculative non-fiction with 'The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of', a wonderful, rowdy Godzilla stomp through the cities of science fiction. Where else could you find Whitley Strieber and John Norman conflated with Robert Heinlein? I'd warn readers not to open this book if they fear seeing the clay feet of their science fiction gods smashed by the bull in the china shop.

|

|

Jeff Vandermeer breaks all sorts of rules in the best possible way with the Prime hardcover version of 'City of Saints and Madmen'. |

And that brings us to the present, or at least, the near-past. Two, count 'em two editions of Jeff Vandermeer's incredible 'City of Saints and Madmen' are currently available. If you can't get the more limited and more expensive hardcover edition from Prime Books, you'll have to settle for the Wildside Press edition. Obviously, our thanks as readers should go out to both houses, but for the speculative non-fiction fan, the Prime Books is the prime choice as it includes lots of extra material and some of the wildest and weirdest fictional non-fiction you're going to happen upon, unless you whip back through time and encounter Thomas Disch while sifting through your dad's Playboy "collection". (Not me! Not ME!) Vandermeer and Prime have put together a publication that defies genre, expectations and reality, all to the reader's great benefit. Including fiction, non-fiction, coded entries, illustration in one of the best designed packages you could hope to hold, 'City of Saints and Madmen' is like a Borges story come to life. Would you like to live in an alternate reality? Let Vandermeer show you how.

But that's what all reading is about, isn't it? We all want to live in an alternate reality. In spite of the most hopeful predictions of the quantum poets and authors, we're not likely to have the technology to do so in our lifetime -- unless you make use of the technology of reading. It's proved to be fairly safe (as long as you don't read and drive) (or read the 'Necronomicon') (or 'The King in Yellow') (or the United States Constitution) (or 'The Communist Manifesto') (or 'The Anarchist's Cookbook')--

OK, so reading is not actually all that safe. You could get put in jail without recourse to a lawyer. It's an extreme sport, then, and it calls for extreme measures. Forget the fiction. Seek out the reality of your choice.

Thanks,

Rick Kleffel